Do one thing (but make it reasonable).

In Defense of Prudence

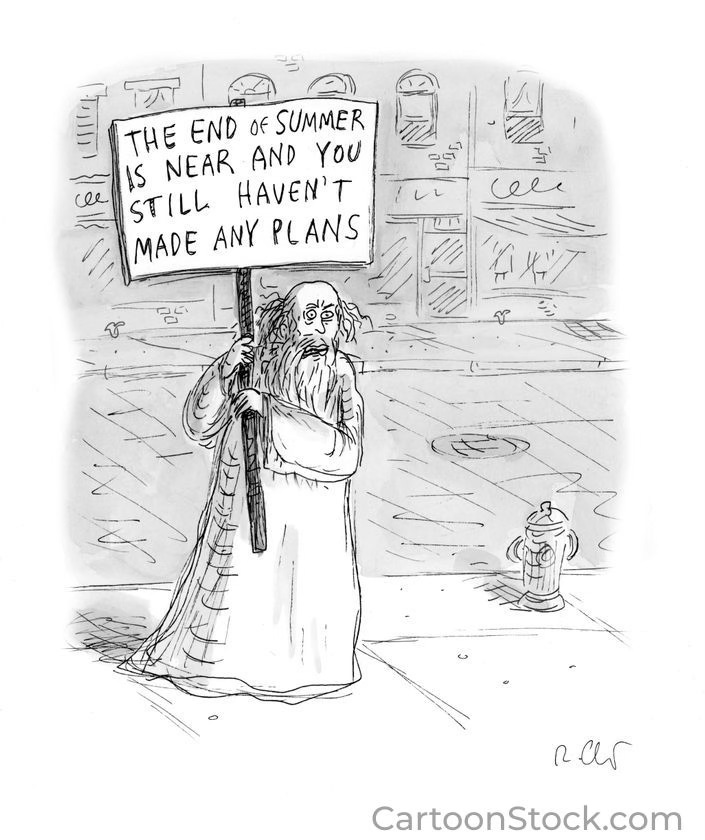

It’s that time of year again.

The back-to-school, new-start energy when it feels like everyone is quietly upgrading themselves. It’s January’s fresh resolve, but with the added pressure of locating lunch boxes and no champagne toast to mark the occasion.

The stores are stocked with tidy plastic planners and color-coded to-do lists, each one whispering: This is the year you will finally get your act together. I promise.

I fall for it every time.

I’m always convinced that summer will fix me. I imagined I’d emerge more rested, more benevolent, more magically able to juggle the chaos of my days. But here I am.

A little more sun-damaged, verryyyy behind on email, and somehow…The Same Me.

We love a good transformation story, don’t we? We binge the podcasts, buy the supplements, and Google how to become a morning person like it’s an emergency. But how much change is actually possible this year? And what does that look like for people with actual lives and jobs and kids and anxiety and Amazon returns? (So many Amazon returns…)

This is the kind of question I live with as a historian of cultural myths. I study what people believe about themselves—and what those beliefs make possible or impossible. Especially when it comes to change.

Are we the captains of our fate, one new habit away from turning it all around? Or are we just along for the ride, hoping not to fall off the edge?

This tension has ancient roots. The Stoics thought we could will ourselves better—prune our desires, master our emotions, control what we could. In the 4th century, St. Augustine wrote that we need divine grace to change at all—virtue, he said, is “a good quality of the mind, by which we live rightly, of which no one can make bad use, which God works in us, without us.”

Somewhere between pure willpower and pure surrender is a space most of us live in—trying to become someone new while knowing we can’t do it all ourselves.

The ancients had a name for the qualities that make a good life possible: the cardinal virtues. Prudence, justice, temperance, and fortitude. These habits of the heart, they argued, are the hinges—cardo in Latin—on which the moral life swings.

Which brings me to my endless defense of the least sexy of the four: prudence.

I know, I know. These days “prude” is an insult reserved for someone who won’t let you watch Outlander in peace. (🚨New Outlander season! Also a prequel! Keep me posted.)

But hear me out about prudence. Prudence is our picker, our internal nudger. And (great news!) we can actually get better at it over time.

In its original sense, prudence is simply wisdom in action: knowing what is good, and then doing it at the right time, in the right way, for the right reasons.

Thomas Aquinas called it recta ratio agibilium, “right reason applied to action.”1 And because it helps guide all the other virtues, Aquinas nicknamed prudence auriga virtutum, “the charioteer of the virtues.” It is not flashy. But it helps justice stay just, temperance stay temperate, and courage be more than bravado.

Aristotle believed we become good by doing good, that habits shape our character over time until virtue becomes second nature.2 This is that slow, real transformation that comes from doing the right thing often enough that it starts to feel like us. Paul echoes this in Galatians 6:9, “Do not grow weary in doing good.” Even psychologists affirm that small habits tied to cues become lasting change.

But Augustine, always the realist, warned that even our best habits can be corrupted if we desire the wrong things. In City of God, he describes how even prudence can be made to serve our appetite for control or approval or pleasure. So we don’t just need the skill to choose well.3 We need the grace to want well.

And maybe the best evidence for slow, grace-soaked transformation is in stories. One of my favorite voices on transformation is Father Greg Boyle, the founder of Homeboy Industries in Los Angeles. He loves to share the story of Louie, a big, joyful presence who spent 18 months in the program before landing a steady job at an air conditioning factory, where he’s worked for the last eight years.

Louie had once been a gang member and, in his words, a “drug dealer to the stars.” But when he left, he said something that stuck with Greg: “You are all diamonds covered in dust.”

That’s what prudence allows us to believe. That we are not finished. That with time, careful wisdom, and a whole lot of love, the shape of our lives can change. The tiny acts we do every day that slowly start to brush away, revealing who we are still becoming.

And not all at once.

In an age of hustle culture, prudence is a quiet rebellion. It reminds us the good life isn’t just what we do, but how and why we do it.

And honestly? It helps keep us from trying in every direction at once. Because trying hard isn’t always the same as choosing well.

As grit researcher Angela Duckworth puts it, “Enthusiasm is common. Endurance is rare.”4

And I have enthusiasm in spades. I’d make an excellent short-term cult member.

Once, in the name of “research,” I joined an online wellness program. Within a week I had the bracelet, the water bottle, and the internal conviction that a new me was just five easy payments away.

Dear Reader, it was not.

But real change, the kind that lasts, is rarely dramatic. It’s small. Repetitive. Often imperceptible. And sometimes? It’s deeply holy.

This fall, I’m trying again. One thing. One reasonable thing.

Last year I tried to read the Bible in a year. I made it to mid-February. This year I’m going smaller. I’m going back to my One Line a Day journal. Just one sentence about my day—some sincere, some medium funny. It’s bite-sized. Doable. A tiny habit that shapes me without exhausting me.

Maybe you’re hungry for something too. Not a whole new you. Just a next step.

Want to pray more regularly? Volunteer? Actually watch your kid’s soccer game instead of scrolling through emails?

Before you decide, let prudence ask:

What do I actually have the energy for?

Does this fit the shape of my actual days?

Is this the kind of growth I need right now?

Am I doing this for the right reason?

If the answer is no, try again. Choose something smaller. Gentler. Wiser.

Choose your One Reasonable Thing and tell me in the comments.

Seriously, I want to hear yours. Let’s cheer each other on, like we are a wellness cult. Without the cult…or the wellness.

And maybe we will change. Slowly. Faithfully. Into someone kinder, more present, and more rooted in something deeper than aspiration or our own desires.

All with a little (internal and divine) nudge.

Listen to this full reflection on Apple or Spotify. Or watch this reflection on YouTube:

For more:

Check out my most recent episode with Father Greg Boyle. I couldn’t be a bigger fan of his if I tried.

I wrote a little blessing for you about this exact kind of change.

Out of ideas? Grab your own One Line a Day Journal and join me.

You should definitely read my friend

’s book The Next Right Thing—a gentle guide to wise, doable steps.

I am on the Alzheimer journey with my husband. I am trying hard, failing often into resentment, anger, and sadness, and needed your reminder. Prudence…I love that description. I keep saying “I’ll do better”, try to give myself grace, but I think I need a reasonable thing, not a generalized “I’ll do better”. That is what I’m going to think about today. Thank you 🙏

My one reasonable thing is to be gentler with my family by guarding my thoughts: when a negative thought pops up ("oh no not this thing again"), I will replace it with a gentle thought.