Living with the Ache

Making Dinner While the World Burns

“We have been waked from a pretty dream, and now we can begin to talk about realities.”

—C.S. Lewis, 1948, “On Living in an Atomic Age”

Thank you, lovely friends, for your comments last week and in particular to Tim Goode, a member of our community who recommended this essay by C.S. Lewis, who has (as we say in the preaching world) A WORD FOR US.

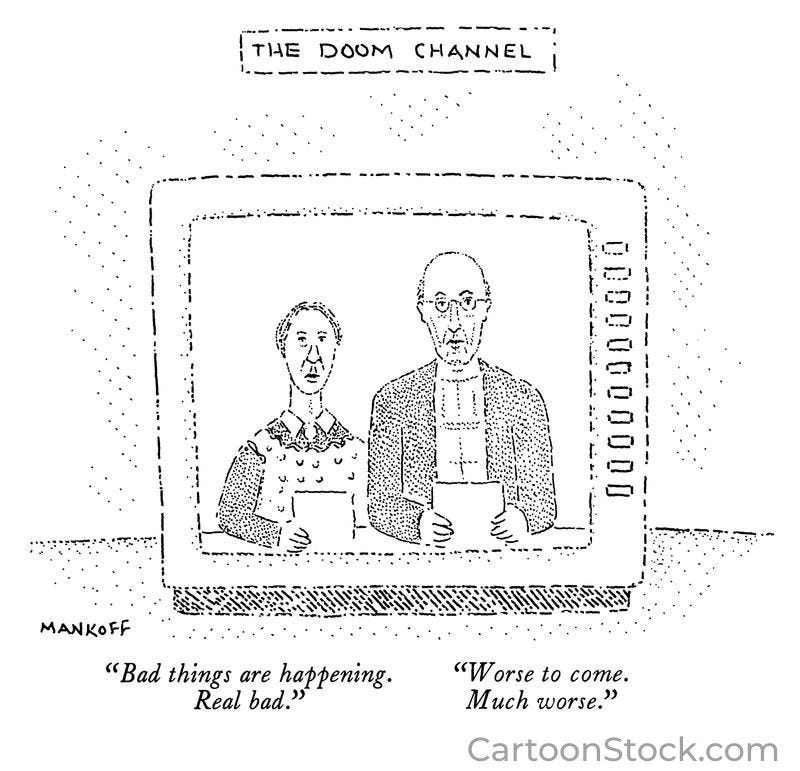

All of us would rather have been doing other things this week—like figuring out how to prevent a soufflé from combusting or finally clearing the snow off the driveway. But instead, we’re like this. Slightly terrified. Slightly glazed. Deeply alarmed.

It’s a strange thing to carry so much grief and… still make dinner.

Still laugh.

Still love people fiercely.

Like you, I’m angry, sad, and worn thin by all the things I can’t fix. I’m watching the news and feeling the familiar churn of helplessness: immigrants targeted and terrified, fear and hatred dressed up as righteousness, the rise of unchecked autocracy.

And still—somehow—we show up to work. We make plans with friends. We put our bodies into chairs and planes and grocery lines. We keep going, even as the ache settles deeper into our bones.

What does it look like to maintain hope and kindness in a world that keeps daring us not to? It’s the question I’ve been chewing over as I feel such dis-ease and despair.

C.S. Lewis wrote the essay quoted above—“On Living in an Atomic Age”—in 1948, when the world was learning to live with the knowledge that it could end itself at any moment. People were afraid, overwhelmed, and tempted toward either frantic distraction or total despair. Lewis did not minimize the danger. Instead, he named the temptation that came with it: the belief that normal life must stop until fear is resolved.

I love what he said about how to live when you’re experiencing a light apocalypse, like we are with our eyes fixed on Minneapolis. “If we are all going to be destroyed by an atomic bomb,” he wrote, “let that bomb when it comes find us doing sensible and human things—praying, working, teaching, reading, listening to music, bathing the children, playing tennis, chatting to our friends.”

Not because danger isn’t real—but because fear does not get to decide what makes us human.

Lewis understood something we are relearning the hard way: that waiting for safety before we live is a losing strategy. “We were born long before the atomic age,” he reminded his readers, “and had, during all those years, been living under the shadow of perpetual threat.”

The world has always been fragile. The illusion was that it wasn’t. Though we are experiencing moral erosion and our awareness is growing with it, this awareness is not meant to paralyze us. Lewis insisted that it is meant to wake us up—to call us back to lives rooted in love, responsibility, and truth, even when outcomes are uncertain.

We are not people who put their heads in the sand. (See the comments section! You are delightful, try-hard neighbors and friends and parents and worker-bees and card-writers.) Or you live with something that cannot be changed, and you couldn’t deny pain if you wanted to. But I’m just grateful for the way you show quiet courage in continuing to care when cynicism would be easier. Like Lewis, we must refuse both hysteria and numbness. He believed that the task of faith in frightening times was not to escape the ache, but to find our own way of living with it.

To keep making dinner.

To keep loving people fiercely.

To keep telling the truth about what hurts without surrendering our capacity for joy.

The world may be on fire—but this, too, is where God meets us. Awake now. Paying attention. Still choosing what is human.

We are heading hard and fast into the season of Lent—it begins on Wednesday, February 18 this year. Lent marks the forty days leading up to Easter, mirroring the forty days Jesus spent in the wilderness. During Lent, we ask God to show us the world as it is.

We begin with the reality of our finitude rubbed on our foreheads on Ash Wednesday—from dust we were made, to dust we shall return. Then, we walk through that reality in a kind of dress rehearsal. It’s the downward slope of God, where the whole Church moves together toward the cross.

Lent does not rush us toward solutions. It doesn’t demand optimism or productivity or a five-step plan for emotional wellness. Lent simply asks us to tell the truth—about who we are, about what hurts, about all that we cannot carry alone.

This year, our Lenten theme is Living with the Ache.

Because so many of us are already doing that.

This constant drip of bad news.

Layered losses.

The guilt of continuing on with ordinary life.

I want to say this gently and clearly: if you feel overwhelmed, you are not weak. You are paying attention.

It feels hard to grieve without a funeral—just a constant low-grade mourning we carry into meetings and grocery lines.

It feels lonely to know so much and still not know what to do.

It feels shameful to have a good day when the world is on fire, as if it were a kind of betrayal.

It feels scary to think that we’re failing at being human—and even scarier to think that we’re not.

It feels impossible to live with a heart cracked wide open in a world that rewards speed and numbness and dissociation. And yet we must.

And so we keep choosing tenderness, even when it costs us something.

We keep choosing courage, even when it costs us something.

We keep doing the next small, ordinary right thing.

We work out our hope like it is a muscle, not a mood.

And somehow, this is how we stay human—together, anyway.

Lent is the season made for exactly a moment like this.

Easter is coming, yes. But for now, we sit in the ashes of our broken dreams and broken hearts, knowing that God sits here with us.

So my dears, this Lent, we won’t rush past the ache.

We won’t apologize for it.

We will learn how to live with it, with enormous hope, together.

I’ll be posting every day throughout Lent right here on Substack. Make sure you’re subscribed. It is totally free.

One word for how things feel lately? You are welcome to use an emoji if you’re already tapped out of words today.

I started my chaplaincy residency in August. It is full time. 40 hours a week. With on call shifts. I have 3 kids with special needs. I live in the Twin Cities. There are so many days over these last two months where just showing up to the hospital feels like a mountain I have climbed and I have zero energy for the day ahead. And then my colleagues and I meet for our morning huddle. And I hear stories of kindness and helpers, and horror and awfulness, the whole gambit. And we laugh, the dry, sardonic laugh of people in hard places. And I decide maybe I can go visit a few patients. When I feel terrible about not doing more than donating groceries for my neighbors too terrified to leave their homes, I tell myself, "We all do what we can. This is what I can do right now." Thank you for the reminder of Lent and lamentation and ashes. Feeling that deeply right now.

When the end of the world is nigh, plant a seed of something you love. - Dwight Lee Wolter.